This is a translation of an article originally published by the weekly news magazine Fokus.

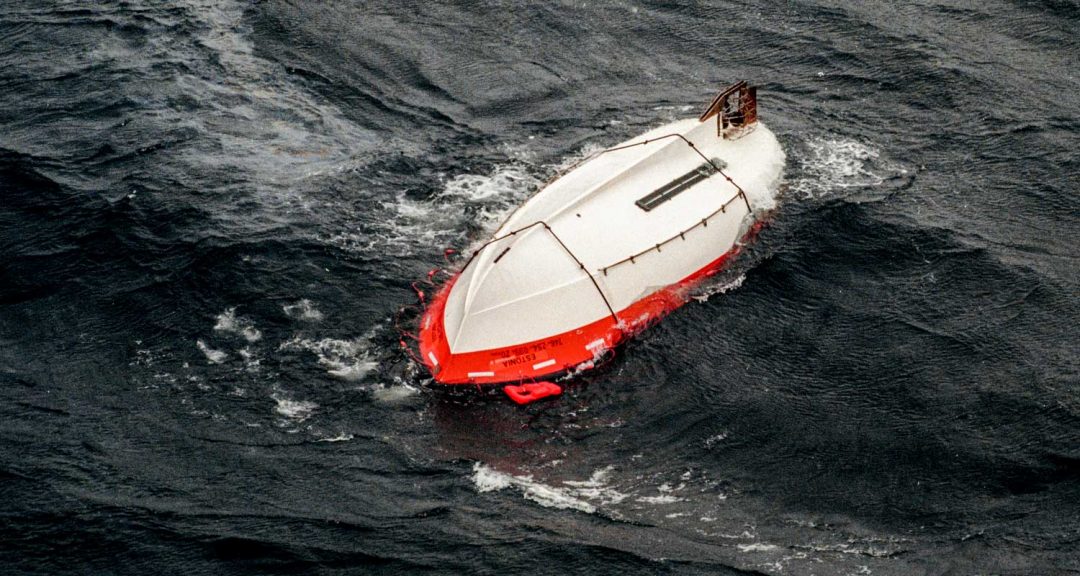

A new discussion about the ship “Estonia”, which sunk in the Baltic in 1994 leaving 852 dead, is underway. Demands for investigations are motivated by new findings on the wreck's condition.

Now, as before, it is claimed that diving at the wreck would be contrary to a joint law for Sweden, Finland and Estonia. It allegedly stipulates that diving to examine the wreck entails a violation of the declared final place of rest, as announced for the wreck.

The claim is unfounded. There is no joint law. Sovereign states do not legislate together. Each state is responsible for its own laws.

Sweden's international commitments can be found in an agreement between Sweden, Finland and Estonia, signed on 23 March 1995. It states:

“The Contracting Parties undertake to institute legislation, in accordance with their national procedures, aiming at the criminalization of any activities disturbing the peace of the final place of rest, in particular any diving or other activities with the purpose of recovering victims or property from the wreck or the sea-bed”

It can be seen that what is criminalized is diving for illegitimate purposes. Diving for legitimate purposes, e.g. to better understand why the ship sank, would by this wording not be hindered by the agreement. That view is asserted from various quarters, e.g. by a Finnish maritime lawyer in January 2020[1] and, as recently as September 29 this year[2], by Estonia's former public prosecutor and Estonian investigator Margus Kurm. Both point out in particular that the agreement does not regulate what the signing powers may undertake. The opposite view also exists, e.g. presented in 2006 by Lauri Mälksoo, Professor of International Law at the University of Tartu. It is important to focus on the agreement and its possible interpretation. Then we can discuss what may and can be done, instead of accepting statements that no action at all is allowed around the ship.

Not least, such a discussion is justified because the wording in the agreement is completely in line with what the former bishop of Stockholm, Caroline Krook, has repeatedly claimed. Namely, that it was not the intention that research on how and why the sinking took place should be prevented following the declaration of peace at the wreck. Instead, the purpose was to give this burial site the same protection that applies to every burial site in Sweden, Finland and Estonia.

With regard to the national laws that were adopted, it can be stated that Estonia in its "ordinary" law on the peace of a final place of rest inscribed the words from the agreement, while Sweden (and Finland) went significantly further and punished all diving, with the exception of actions planned just when the law was adopted. Those actions were to cover the wreck with concrete, or something else intended to cover the wreck, and to empty the wreck of oil.

Nowhere in the preparatory works for the Swedish law is there any explanation as to why it goes so much further, being so much more restrictive than the wording in the agreement. On the contrary, the words in the bill 1994/95: 190, give the impression that it is the agreement reached that is being implemented. And the criminalization of measures at the wreck is presented as if the measure is similar to what applies in the "ordinary" Swedish law on the peace of a final place of rest. But that law only criminalizes unauthorized disturbance of the peace.

A recapitulation of the time and context in which the agreement and law came into being provides guidance to better understand their design

- The question of salvaging the wreck was raised immediately after it sank on September 28, 1994. Prime Minister Carl Bildt and incoming Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson promised that the ship would be salvaged and the dead given a dignified burial.

- Assignments were given to the Swedish Maritime Administration. The government also appointed an ethics council, one of whose members was Bishop Caroline Krook. The Swedish Maritime Administration reported on 14 December 1994 that it was possible to salvage the ship but that it would encounter problems. The same day, the Council of Ethics advised against salvage and recommended that the crash site be declared a burial site.

- On 15 December 1994, the Government, after consultation with the governments of Estonia and Finland and the leaders of the parties represented in parliament, announced that no rescue would take place. The government decided that the ship would be covered to prevent looting.

- Many protested. The main argument against a cover was that it would forever be impossible to further investigate the wreck.

- The government immediately contacted Estonia and Finland to win approval for the Swedish plans.

- At a meeting on 16 January 1995 in Stockholm, it was agreed that the three countries individually would penalize activities that disturb the peace of the wreck and that an international agreement setting out the framework for such legislation would be concluded. An agreement was signed on 23 February 1995

- In the light of the agreement, a memorandum was drawn up within the Ministry of Justice dated 28 February 1995 on the protection of peace for the burial site “Estonia”. The memorandum was the subject of a hearing in the Ministry of Justice on 9 March 1995. The Law Council (Sw. Lagrådet)delivered its opinion on 20 March and the Government decided on 30 March on Bill 1994/95: 190

This description shows a hectic time full of stress for everyone involved. In a few months, promises of salvage had been made, proved not be possible to fulfill, were exchanged for decisions on coverage of the wreck, all of which called for repeated deliberations with Estonia and Finland and a lot of work on an agreement and a law.

It is only natural that both agreements and Swedish law were marked by the time when they came into being. There was a Swedish decision to cover the wreck. Such coverage was expected to take place relatively soon.

With this observation, the intergovernmental agreement gets its natural explanation. The agreement regulates what needed to be regulated, namely to both approve that Sweden would cover the wreck and, in the meantime, to prevent looting from private actors. It was not necessary to regulate how decisions could be made on any further investigations, since no further investigations could be undertaken, once the ship was covered.

These observations also provide a basis for understanding the Swedish law. Unlike what happened in Estonia, going beyond the wording of the agreement could be explained by the fact that the work went too fast, that details were overlooked. Or simply left aside because in practice the law would only matter until the wreck was covered. In substance, however, what happened is still inexplicable because the law's preparatory works does not even touch on this difference between agreement and bill.

Now it is not decisive that agreement and law look the way they do. But a review is needed to realize that both the agreement and Swedish law have lost touch with reality. The decision to cover was revoked in 1996, but the wreck remains. That three states would have decided to bind themselves and each other forever in order not to make any further investigations is not reasonable. To claim that such general obstacles would be appropriate to protect the peace of the burial site is unfounded. Estonia, Finland and Sweden all have regulations that permit graves being opened if there are objective and duly tried reasons for doing so.

A new agreement that is adapted to reality is needed, regardless of what new observations of the wreck may appear one day or the other. "Expert authorities" have nothing to do with the matter.

Sweden was the driving force in the development of events in 94/95. It is Sweden's responsibility to take the initiative for a new agreement. And it is urgent in order to relieve the country of Estonia being compelled to move forward on its own.

______

Karl Gustaf Scherman, formerly State Secretary, Hospital Director, Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm, Director General The National Insurance Board, President of the International Social Security Association.

Scherman had extensive contacts with Estonia after the liberation from the Soviet Union in the 1990’s.

A new discussion about the ship “Estonia”, which sunk in the Baltic in 1994 leaving 852 dead, is underway. Demands for investigations are motivated by new findings on the wreck’s condition.

Now, as before, it is claimed that diving at the wreck would be contrary to a joint law for Sweden, Finland and Estonia. It allegedly stipulates that diving to examine the wreck entails a violation of the declared final place of rest, as announced for the wreck.

The claim is unfounded. There is no joint law. Sovereign states do not legislate together. Each state is responsible for its own laws.

Sweden’s international commitments can be found in an agreement between Sweden, Finland and Estonia, signed on 23 March 1995. It states:

“The Contracting Parties undertake to institute legislation, in accordance with their national procedures, aiming at the criminalization of any activities disturbing the peace of the final place of rest, in particular any diving or other activities with the purpose of recovering victims or property from the wreck or the sea-bed”

It can be seen that what is criminalized is diving for illegitimate purposes. Diving for legitimate purposes, e.g. to better understand why the ship sank, would by this wording not be hindered by the agreement. That view is asserted from various quarters, e.g. by a Finnish maritime lawyer in January 2020[1] and, as recently as September 29 this year[2], by Estonia’s former public prosecutor and Estonian investigator Margus Kurm. Both point out in particular that the agreement does not regulate what the signing powers may undertake. The opposite view also exists, e.g. presented in 2006 by Lauri Mälksoo, Professor of International Law at the University of Tartu. It is important to focus on the agreement and its possible interpretation. Then we can discuss what may and can be done, instead of accepting statements that no action at all is allowed around the ship.

Not least, such a discussion is justified because the wording in the agreement is completely in line with what the former bishop of Stockholm, Caroline Krook, has repeatedly claimed. Namely, that it was not the intention that research on how and why the sinking took place should be prevented following the declaration of peace at the wreck. Instead, the purpose was to give this burial site the same protection that applies to every burial site in Sweden, Finland and Estonia.

With regard to the national laws that were adopted, it can be stated that Estonia in its ”ordinary” law on the peace of a final place of rest inscribed the words from the agreement, while Sweden (and Finland) went significantly further and punished all diving, with the exception of actions planned just when the law was adopted. Those actions were to cover the wreck with concrete, or something else intended to cover the wreck, and to empty the wreck of oil.

Nowhere in the preparatory works for the Swedish law is there any explanation as to why it goes so much further, being so much more restrictive than the wording in the agreement. On the contrary, the words in the bill 1994/95: 190, give the impression that it is the agreement reached that is being implemented. And the criminalization of measures at the wreck is presented as if the measure is similar to what applies in the ”ordinary” Swedish law on the peace of a final place of rest. But that law only criminalizes unauthorized disturbance of the peace.

A recapitulation of the time and context in which the agreement and law came into being provides guidance to better understand their design

- The question of salvaging the wreck was raised immediately after it sank on September 28, 1994. Prime Minister Carl Bildt and incoming Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson promised that the ship would be salvaged and the dead given a dignified burial.

- Assignments were given to the Swedish Maritime Administration. The government also appointed an ethics council, one of whose members was Bishop Caroline Krook. The Swedish Maritime Administration reported on 14 December 1994 that it was possible to salvage the ship but that it would encounter problems. The same day, the Council of Ethics advised against salvage and recommended that the crash site be declared a burial site.

- On 15 December 1994, the Government, after consultation with the governments of Estonia and Finland and the leaders of the parties represented in parliament, announced that no rescue would take place. The government decided that the ship would be covered to prevent looting.

- Many protested. The main argument against a cover was that it would forever be impossible to further investigate the wreck.

- The government immediately contacted Estonia and Finland to win approval for the Swedish plans.

- At a meeting on 16 January 1995 in Stockholm, it was agreed that the three countries individually would penalize activities that disturb the peace of the wreck and that an international agreement setting out the framework for such legislation would be concluded. An agreement was signed on 23 February 1995

- In the light of the agreement, a memorandum was drawn up within the Ministry of Justice dated 28 February 1995 on the protection of peace for the burial site “Estonia”. The memorandum was the subject of a hearing in the Ministry of Justice on 9 March 1995. The Law Council (Sw. Lagrådet)delivered its opinion on 20 March and the Government decided on 30 March on Bill 1994/95: 190

This description shows a hectic time full of stress for everyone involved. In a few months, promises of salvage had been made, proved not be possible to fulfill, were exchanged for decisions on coverage of the wreck, all of which called for repeated deliberations with Estonia and Finland and a lot of work on an agreement and a law.

It is only natural that both agreements and Swedish law were marked by the time when they came into being. There was a Swedish decision to cover the wreck. Such coverage was expected to take place relatively soon.

With this observation, the intergovernmental agreement gets its natural explanation. The agreement regulates what needed to be regulated, namely to both approve that Sweden would cover the wreck and, in the meantime, to prevent looting from private actors. It was not necessary to regulate how decisions could be made on any further investigations, since no further investigations could be undertaken, once the ship was covered.

These observations also provide a basis for understanding the Swedish law. Unlike what happened in Estonia, going beyond the wording of the agreement could be explained by the fact that the work went too fast, that details were overlooked. Or simply left aside because in practice the law would only matter until the wreck was covered. In substance, however, what happened is still inexplicable because the law’s preparatory works does not even touch on this difference between agreement and bill.

Now it is not decisive that agreement and law look the way they do. But a review is needed to realize that both the agreement and Swedish law have lost touch with reality. The decision to cover was revoked in 1996, but the wreck remains. That three states would have decided to bind themselves and each other forever in order not to make any further investigations is not reasonable. To claim that such general obstacles would be appropriate to protect the peace of the burial site is unfounded. Estonia, Finland and Sweden all have regulations that permit graves being opened if there are objective and duly tried reasons for doing so.

A new agreement that is adapted to reality is needed, regardless of what new observations of the wreck may appear one day or the other. ”Expert authorities” have nothing to do with the matter.

Sweden was the driving force in the development of events in 94/95. It is Sweden’s responsibility to take the initiative for a new agreement. And it is urgent in order to relieve the country of Estonia being compelled to move forward on its own.

______

Karl Gustaf Scherman, formerly State Secretary, Hospital Director, Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm, Director General The National Insurance Board, President of the International Social Security Association.

Scherman had extensive contacts with Estonia after the liberation from the Soviet Union in the 1990’s.